Discover more from MTS Observer

A Monstrosity of Malinvestment - Apartment Bridge Loans from 2021-2022

"...statistics in the Las Vegas multifamily market, for example, suggest 43 active projects originated with bridge loans. Of those 43, 20 (47%) are distressed..."

For roughly an 18-month period between early 2021 and late 2022, the multifamily real estate investment market (i.e., apartments) was gripped by extreme malinvestment, coupled with perversions in lending standards, the likes of which haven’t been seen since 2008.

In Austrian economics, malinvestment is a misallocation of resources caused by the excesses of a fiat regime, typically a combination of loose monetary policy, low interest rates and fiscal profligacy.

All three of the abovementioned causal factors have been on full display recently, during the ZIRP (Zero Interest Rate Policy) era, particularly as the Federal Reserve teamed up with the Biden administration to further bloat the Fed balance sheet from an already obese 4 Trillion (which was itself a massive increase from the baseline level of roughly 900 Billion pre-2009) to 9 Trillion and throw “stimulus” checks directly at consumers and businesses of all sizes in the wake of the coronavirus panic initiated by the Trump administration.

Cause and Effect

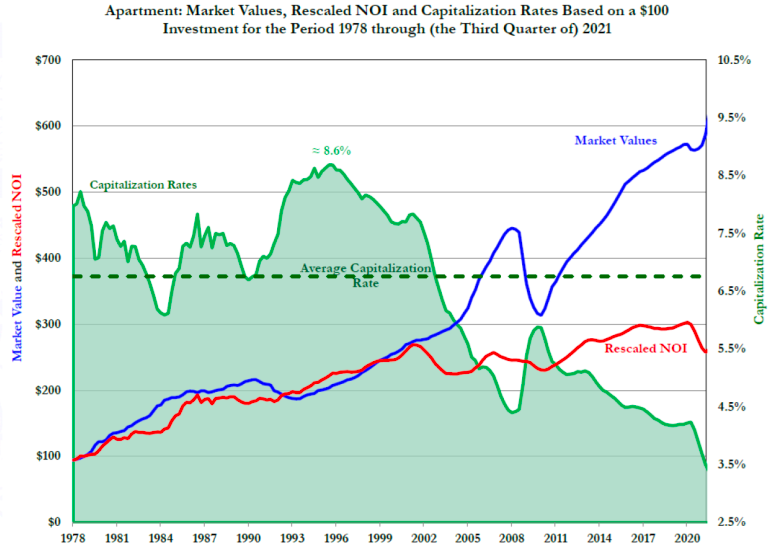

As one direct consequence of this meddling, Cap Rates (a measure of the initial profitability of a real estate investment, as measured by the ratio of Net Operating Income to Purchase Price) were driven to unprecedented lows from already historically low levels.

Apartment investment loans have traditionally been provided by HUD, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (“the Agencies”). This market, like so many others where a “basic need” like housing is involved, has been dominated by the government and barely resembles a market in the true sense. Nevertheless, historically, traditional apartment financing has consisted of loan-to-value ratios in the 65-75% range, with the investor putting up the remaining 25-35% of funds (plus transaction expenses) as equity.

However, as cap rates have materially declined (i.e., prices have increased at a faster rate than underlying profitability), the Agencies were no longer able to loan up to 75% of the purchase price, potentially causing investors to fund a larger portion of the purchase price via equity, thus diluting their returns.

Introduction & Dominance of Bridge Loans

In the absence of the Agencies, and to provide financing for insatiable apartment investors at leverage ratios they were used to, bridge loans became a ubiquitous high-leverage tool for investors (and their all too willing debt brokers), with an estimated 80% share of apartment loan originations in the 2021-2022 timeframe.

While bridge loans, per se, have been around for as long as lending and don’t necessarily conform to a specific set of features, this class of bridge loan carried fairly standard terms that may ring a bell for those of us who lived through the 2008 credit crisis. Investors were typically able to borrow up to 85% of purchase price plus all future capital expenditure, and generally influence loan terms based on pro forma expectations for rent growth and other metrics. As one can imagine, pro forma expectations can mean any number typed into a spreadsheet.

As with home mortgages of the 2004-2007 era, apartment bridge loans generally offered fixed-rate, interest-only periods initially but moved to floating rates (or simply matured) after 1-3 years, leaving investors with a small window in which to either drastically improve income or exit the project (i.e., sell to a greater fool), lest higher benchmark rates destroy their returns and put them under water.

Beginning of the End

Ignoring the moral hazards associated with this type of lending (most notably, mediocre and unethical sponsors with no skin in the game taking advantage of yield-chasing but unsophisticated investors, and loan originators with no skin in the game securitizing and selling the loans to yield-chasing but unsophisticated investors – both earning high fees in the process), the inevitable conclusion is distress in this asset class once benchmark interest rates reset to more normal levels and asset values subsequently decline. Both have happened in recent months, with benchmark rates up roughly 400bps in the last 18 months and cap rates moving back towards the long-term trendline, though still below it by a fair margin.

While most of these bridge loans have yet to mature or adjust to higher rates, there are already clear signs of distress. Industry analysis of CLOs (collateralized loan obligations, essentially securities made up of the bridge loans underlying the acquisitions discussed herein) and related statistics in the Las Vegas multifamily market, for example, suggest 43 active projects originated with bridge loans. Of those 43, 20 (47%) are distressed, with Net Operating Income below current debt service needs.

Austin, arguably the country’s most fundamentally attractive and robust multifamily market, shows greater resilience than Las Vegas but weakness nonetheless. In that market, industry analysis suggests 150 active projects originated with bridge loans (and subsequently packaged into CLOs), of which 32 (21%) are, at least on paper, unable to service debt. A separate Austin analysis from a primary source showed 20-34 projects financed by bridge loans on lender “watchlists.”

Downside Case

Considering the already clear distress, it’s hard to imagine things working out well for the sponsors and investors involved (especially the investors, as the sponsors have already been paid the bulk of their fees), but how and when will things come apart? To what extent will the effects be felt elsewhere in the market? Will the unraveling of these distressed loans ultimately provide real value for multifamily investors, of a kind that hasn’t been seen in many years? Or will the Fed step in again to “ease conditions”, thus reinflating the asset bubble that’s existed for the last 15 years? These questions are yet to be answered, but it’s unlikely that a free market will be allowed to determine the outcome.

Some truly disturbing distortion in the system. I wonder whether government and regulatory bodies will even be able to intervene and shape market outcomes in the future given repeated abuse of the power, a weakening dollar and potential market volatility or economic shocks.